Background

Credit: Neil Rutledge

The excellent article Distributed map in EUTXO model from Marcin Bugaj describes the need for an on-chain, distributed data structure which can guarantee uniqueness of entries.

If you want to validate that something doesn’t exist on chain in the EUTXO model, you do not have access to anything aside from the transaction inputs, which are limited by transaction size limits. So checking that someone hasn’t voted twice, for example, would be impossible without some sort of data structure that can guarantee uniqueness on insert.

A potential solution, heavily inspired by the distributed map idea, is described below that shares the following properties with the distributed map:

- Verifiable uniqueness of keys on chain

- Verifiable traversal on chain

However, it has a couple key advantages:

- Constant time (single transaction) insert/removal with low contention

- Sorted entries

Overview

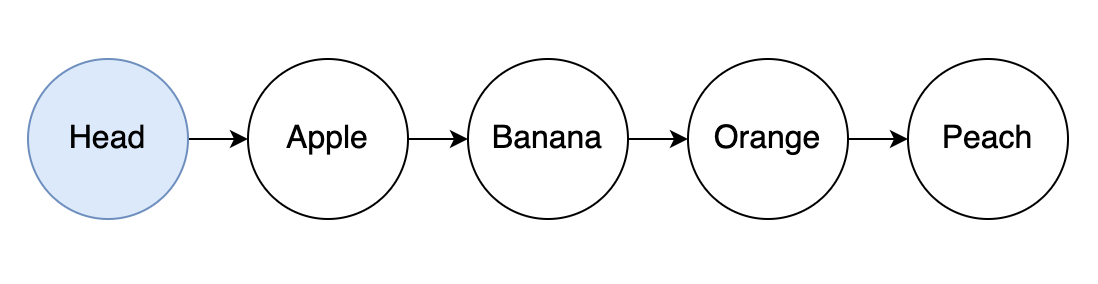

The solution consists of an on-chain, sorted, linked list of key/value entries.

Each entry in the list will consist of an NFT and a datum with the key, value and pointer to the next NFT in the list (more details explained later).

Inserting an Entry

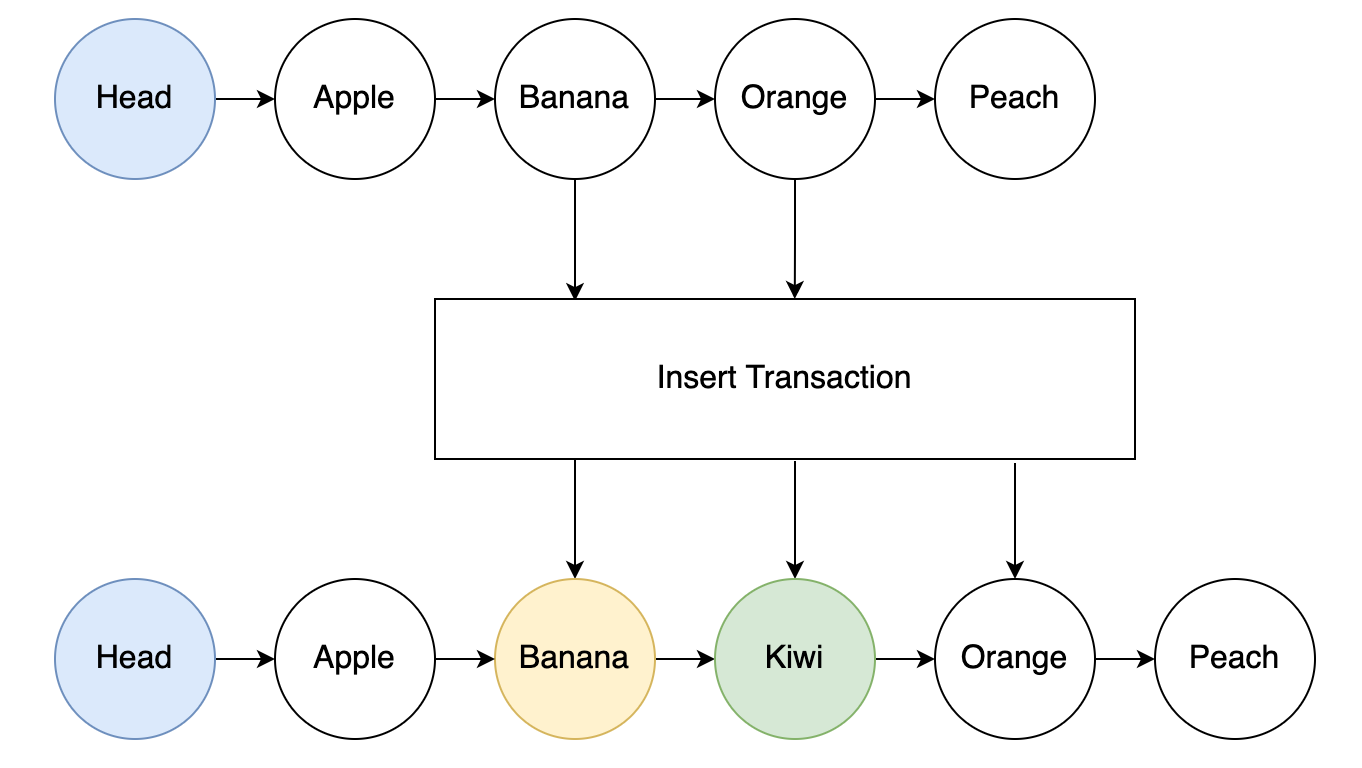

If we want to perform an insert operation that can be validated on chain to ensure no duplicate entry occurs, we can simply create a transaction with two adjacent items as inputs like so:

The transaction outputs would be:

- The first entry from the inputs, now pointing to the new entry

- The new entry, pointing to the second input entry

- The second entry from the inputs, unchanged

To ensure uniqueness, the script will validate that the following conditions are true:

- a < b < c

- input a points to input c

- output a points to output b

- output b points to output c

Where a = lowest input key, b = new key and c = highest input key.

As you can see, it is extremely simple to prove/validate whether or not a given key exists by inspecting two adjacent keys and checking if the new key fits between those according to the ordering.

An empty head entry can be used for validating inserts at the start of the list (i.e., the head and first entry must be inputs and the new entry must have a key lower than the first entry’s key).

For inserting at the end of the list, the script can simply validate that the input entry points to nothing and that the new entry key is higher than the input entry’s key.

Removing an Entry

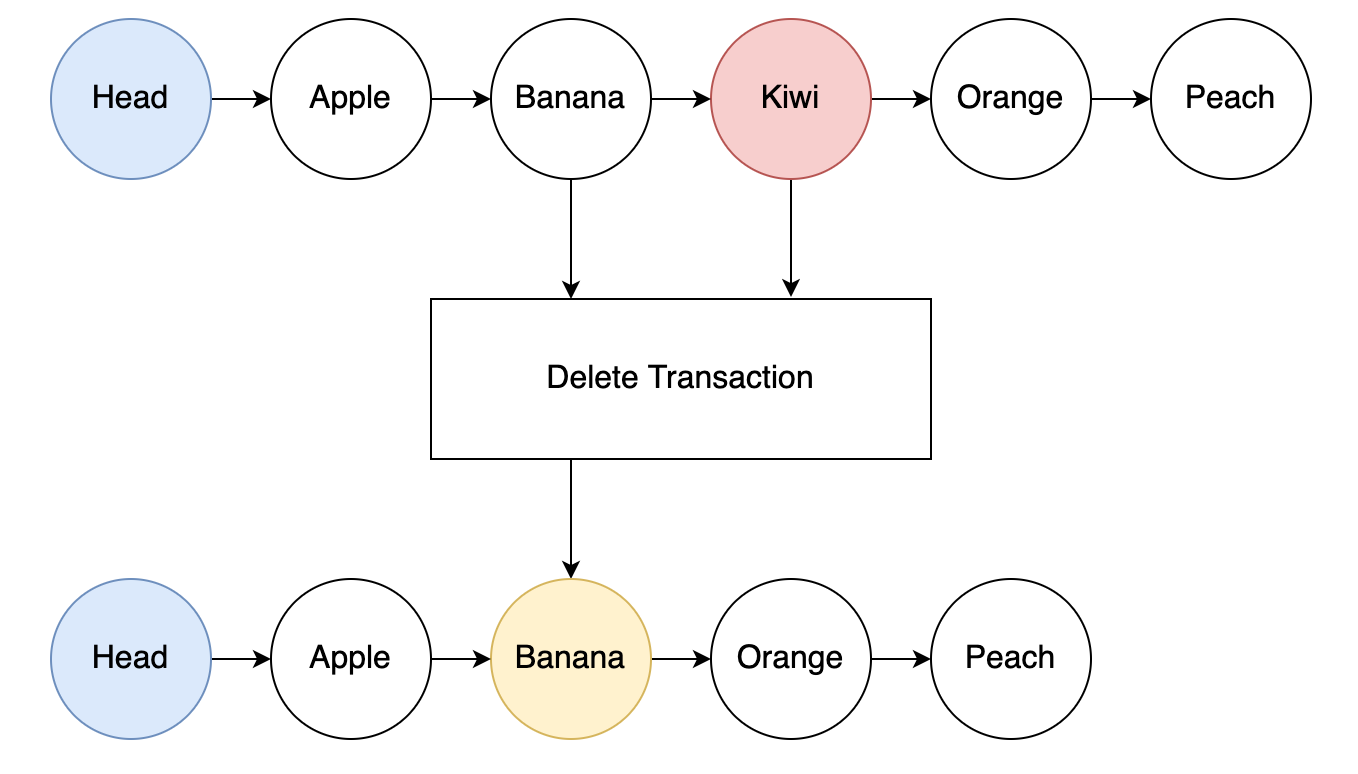

If we need to remove an entry from the list, the process is even simpler.

The transaction inputs in this case would be the entry to be removed and the previous entry.

The removed entry NFT could be burned and the output would be the previous entry now pointing to what the removed entry was pointing to.

Wait, looking up entries would be horribly inefficient!

Yes, it is true that a linked list is a very inefficient data structure for performing lookups. But since lookups will be done off-chain, it doesn’t really matter. A more efficient data structure could be maintained off-chain for lookups if that’s required. The key here is that the operations on chain only take a single transaction and as few inputs/outputs as possible.

Datums and Redeemers

The following are examples of what the datum and redeemer types could look like.

type NFT = AssetClass

data EntryDatum = EntryDatum

{ key :: BuiltinByteString

, value :: Maybe SomeValue

, nft :: NFT

, next :: Maybe NFT

}

data Redeemer

= Insert SomeValue

| Use

| Update SomeValue

| Remove

The EntryDatum holds the key/value pair for each entry. In the case of the head entry, the value would be Nothing. Each EntryDatum also points to the NFT that identifies the entry, as well as the next NFT in the list that this entry points to (which is Nothing for the last entry).

Each EntryDatum could also hold the key of the next entry, thus eliminating the need to pass in the second entry when performing an insert (since only the key is required for validation and nothing changes for that entry).

NFTs as Pointers

An important question now is: where do the NFTs come from and how can we ensure they are unique?

One way to achieve this would be to first mint the head NFT and then use its AssetClass or CurrencySymbol as a parameter for both the entry NFT minting policy and the script that locks them. This will create a unique script hash for each list as well as unique NFT CurrencySymbols for each list. The minting policy can validate that either the head NFT is spent or an entry that it minted is spent before minting any further entry NFTs. The script can also validate that each NFT added has the correct AssetClass (they will all share the same CurrencySymbol but should have a unique TokenName such as a hash of the key).

Plutus also has a forwardingMintingPolicy (described here: Forwarding Minting Policy) that could potentially work.

How About Using Datum Hashes as Pointers?

Using the the DatumHash sounds very convenient as a pointer, but there is a problem in that updating one entry will change its hash, thus requiring the parent’s pointer to be updated, as well as its parent, and so on all the way up to the head entry.

It may then be tempting to use a hash of all fields, excluding the next field, but this has another problem: someone could easily create a malicious EntryDatum that hashes the same as another but points to some sublist of malicious entries.

So it seems using datum hashes is out of the question as a standalone option (though this could work in combination with NFTs).

Folding/Traversing Over the List

Since the data structure forms a linked list, folding/traversing is extremely straight forward. However, if you need to verify that the entire list has been traversed on chain, you’ll need some way of building up a proof from several transactions.

Let’s look at how we would prove that the entire list has been folded over using a new datum.

data FoldingDatum a = FoldingDatum

{ start :: NFT

, next :: NFT

, nft :: NFT

, accum :: a

}To create this FoldingDatum, you would spend one or more list entry UTXOs in a transaction. A validation rule would check that the spent entry UTXOs form a valid linked list and that the output FoldingDatum contains:

-

start = the first input entry’s

nftfield -

next = the last input entry’s

nextfield - nft = a reference to a new NFT identifying the FoldingDatum and providing proof that it is valid

- accum = whatever value you want to accumulate

The FoldingDatum can now be used in another transaction that starts with the next entry and consumes some number of additional entries (however many fit in the transaction). The start value will remain the same throughout this process, but the next will point further down the list after each transaction until reaching Nothing at the end of the list.

Parallel Folds

Folding over a list using a single datum over a series of blocks is certainly an option, but we can do better. Instead of creating a single FoldingDatum, we can create n FoldingDatums in parallel that each consume different sections of the list.

Imagine that there is a list of 1000 entries and 100 FoldingDatums are created that each consume 10 entries as 100 parallel transaction. The following example will represent the FoldingDatums as (start, next) tuples.

(head, 10) (10, 20) (20, 30) (30, 40) (40, 50) (50, 60) ... (990, Nothing)In another block, assuming we can fit 10 inputs per transaction, the 100 FoldingDatums could themselves be folded into 10 FoldingDatums.

(head, 100) (100, 200) (200, 300) (300, 400) (400, 500) ... (900, Nothing)These 10 FoldingDatums can finally be folded into a single datum.

(head, Nothing)Since this whole process was controlled by validation rules that confirm the validity of each FoldingDatum, the final result serves as a proof that all entries were included, which can be used by a smart contract to verify on chain that all votes have been counted, for example. And this whole process happened in O(log n) time:

- Constant time creation of FoldingDatums (parallel transactions in one block)

- Logarithmic time merging of FoldingDatums

The off-chain logic will have to traverse the list in O(n) time in order to create the transactions involved but, again, we aren’t really concerned with the off-chain efficiency.

Note: For really big lists, you’ll be bumping up against the fundamental TPS limits of the blockchain, so some of these operations will take additional blocks.

Handling Contention / Race Conditions

One additional thing that needs to be considered here is how to handle contention on UTXOs during the folding/traversal process. This could result in failed transactions as well as unexpected behaviour from the list changing part way through.

A few potential options:

- Require that the head token is spent during each insert/update/removal and put a lock field in the datum to allow locking the list in a read-only mode. (Need to consider when the list is allowed to be unlocked, whether there should be a timeout, etc.)

- Similar to the first option, require the head token to be spent for each insert/update/removal, but instead of using a lock field, maintain an incrementing version number in the head datum as well as the version of each entry. This way, a version number can be declared in the FoldingDatum, which would allow skipping over entries with higher version numbers. Deleted entries would need to be kept around with some sort of deleted status.

-

(h v5) -> (apple v3) -> (banana v1) -> (kiwi v2 deletedInV4) -> (kiwi v5) - Don’t lock the list or require spending of the head entry (which will have contention on it making it difficult to even set the lock) and instead include approximate timestamps on each entry. With a few modifications (such as including the ability to have entries branch off to different versions) this could be turned into an immutable data structure that maintains the full version history.

Note: If there is a need for shared state that is limiting throughput, things like queuing and batching can be introduced as well.

Summary

This document glossed over some details for the sake of brevity but it has outlined what I feel is an elegant approach to working with on chain data that has uniqueness guarantees and is also extremely efficient to maintain on-chain.